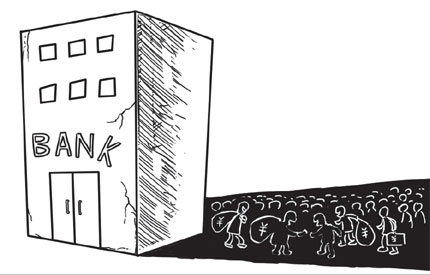

For a long time Wenzhou in Zhejiang Province, a hub of private enterprises, has arguably been a poster child of China's robust private sector. Yet the recent cash flow debacle that unfolded there has seriously called that perspective into doubt.

Twenty-nine business owners have fled Wenzhou, leaving behind a huge pile of outstanding debts. As of August, the aggregate number of debt defaults had surged 25.73 percent from the same period last year and the money at stake amounted to over 5 billion yuan (US$733 million).

The desperate situation has prompted the central government to intervene to bail out Wenzhou's struggling small firms.

Given this bleak picture, the booming underground financing in Wenzhou is an anomaly. The Wenzhou branch of People's Bank of China, the country's central bank, found in a recent survey that "shadow banks" in Wenzhou have 110 billion yuan at their disposal, with 89 percent of local families and individuals and nearly 60 percent of firms involved in the credit trade.

The central bank's conclusion is that "underground financing has become the primary investment alternative to real estate." Shadow funding has pulled in huge funds for private equities in some locales. The promise of high return, at a staggering ratio of 10 or even 100 times the original investment, has attracted money-rich investors tired of the sluggish stock and property markets.

Cash-strapped banks have no choice but to release high-risk financial products to win back customers drawn to the lucrative shadow credit business. At a time when credit tightening has considerably cramped the money flow, we can still see some investment projects netting more money than expected.

This is an indication that China doesn't really have a cash flow problem. A lot of idle money has even poured into the commodities market and pushed up prices of agricultural products and industrial raw materials - the last thing state regulator wants to see.

The speculative run has complicated efforts to combat inflation and forced the central bank to roll out measures aimed at draining liquidity. But the contrast between a cash-strapped Wenzhou and a cash-awash Wenzhou has called to mind the limits of credit tightening.

A majority of the medium and small enterprises that suffer a credit crunch today are those impacted by the nation's industrial overhaul in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. They are regarded as redundant and obsolete because of their high operational costs, vast energy consumption, severe pollution and low output.

The increase of fuel and utility prices and the rapid appreciation of the yuan, together with the forced brownouts to meet green goals in some areas, combine to make life more difficult for them. Many expected these small companies, with high maneuverability, to lead the industrial restructuring and upgrading. That's not happening. What we see instead is they are tripped by predicaments of the transition.

Some companies withdrew from the real economy long ago. With industrial capital and cheap bank loans secured through collateral, they have invested in real estate, commodities, art collection, vintage wines, and private equities in anticipation of high yields. But if these investment choices don't work out, credit problems arise. The indebted businesses have to either sell their assets or borrow on usurious terms to service loans. They appear to have chosen the second option to fill funding shortfalls.

Therefore, should they stop relying on shadow banks for high-interest loans, these banks will collapse since legal banks' interest rate is in fact negative - meaning inflation outpaces benefits accruing from depositors' bank savings.

Businesses that didn't make the leap into the capital market have bided their time in the hope that an industrial spring will arrive one day. But their talent pool is shallow, and they don't have deep pockets. So an industrial spring is still just a dream.

Even though they may have many orders to fill, they decide to hunker down in the face of soaring labor costs, a shortage of skilled labor, and escalating trade frictions - rather than take a shot at their ambition.

A direct result of the central bank's tightening measures is the rocketing interest rate charged on loans. The new loan sharks thus can earn big money in a short period of time, even accumulating the equivalent of a year's operation of their former legitimate business.

Polluting as ever

Under such circumstances, some regions or firms ill-suited to develop renewable energies have eagerly done just that, in pursuit of cheap state loans and support. Foreigners are well aware of this and they have outsourced their production work, which is not in any sense clean, to China where they have benefited from low prices due to fierce local competition.

Now we realize the large hidden costs, but it's too late. Moreover, recently the alarm has been raised about the overproduction in this sector. Small companies are nominally engaged in a clean energy revolution and think they have finally achieved high added value, but as a matter of fact they have not. They have yet to transcend their traditional role of sub-contractors and suppliers of cheap goods and services.

The homogenizing trend in tapping green technologies has led to an excess of state subsidies being poured into risky enterprises and the so-called "new economy," rather than into industries that have a competitive edge and are hungry for funds.

The latest round of inflation is born of rising costs. Many companies with their footing in the real economy feel the pinch and because of a herd mentality and a desire to distribute risks, they have tentatively placed some money on the gambling table of the capital casino, which contributes to the "cash famine" besetting the real economy.

To solve the problem of "cash famine" and "cash glut," I proffer some policy recommendations in hopes that relevant authorities might draw on them and implement a raft of schemes that work better than credit tightening alone.

Solutions

First, achieving high added value is our long-term goal but now China is seriously lacking in talent, capital and financial sophistication.

So putting all the eggs in a single basket of incubating green technologies only wastes resources and engenders vicious competition. In fact, some enterprises are capable of achieving high added value but they are discriminated against by regional policies. We should reduce their tax burden and logistics costs and give them equal opportunities to compete.

Second, we need to beef up supervision to prevent the financial sector from sucking industry dry of its fuel. Otherwise serious stagflation will emerge. In the meantime, full government support for businesses that don't dally with shadow credit will help reinvigorate their growth and offset the spillover effect of "negative" interest rate.

Third, we need to craft better institutional responses to the problem of sloshing liquidity. To do so entails tax incentives and the expertise of financial professionals to channel excessive capital from finance to the real economy. However, there's a caveat. It was the immoral practices of financial wizards, coupled with systematic opaqueness, that created the US sub-prime mortgage fiasco.

So when we seek the help of financial professionals in managing idle capital, it is necessary to strengthen oversight because their irregularities are deadlier than ill-considered investments by retail investors. Financial maturity is central to the success of China's economic transition.

Source:china.org.cn